Certain bridges seem perfectly suited to their locations. Ever wonder why?

It’s because design and engineering come together to create structures that are ideal for their settings.

In this two-part series, we’re looking at the four most popular bridge types, how they work, the locations they’re ideal for, the benefits of each, and amazing examples across the globe.

Suspension Bridges

Everyone loves looking at — and traveling over — suspension bridges. They’re elegant, light, and airy yet strong. Suspension bridges and their variations are able to span longer distances than any other type of bridge.

Is there a more iconic suspension bridge — or bridge of any type — than the Golden Gate in San Francisco?

Is there a more iconic suspension bridge — or bridge of any type — than the Golden Gate in San Francisco?

Unfortunately, they’re also typically the most costly to build.

So, how does a suspension bridge work?

As the name suggests, this type of bridge suspends the roadway from cables, which extend from one end of the bridge to the other. The cables rest on top of towers and are secured at the ends of the bridge by anchorages.

The towers make it possible for engineers to stretch the main cables across very long distances. The towers and cables also carry most of the weight of the bridges. The weight is transferred to the anchorages, which are typically embedded in solid rock or large blocks of concrete. Within the anchorages, the cables are spread over a relatively large area to better distribute the load. This helps prevent the bridge cables from breaking free, which would cause the structure to fail.

Believe it or not, the earliest cables used to support suspension bridges were made from twisted grass. By the beginning of the 19th century, engineers started using iron chains to suspend the road beds.

Today, the cables of suspension bridges are made from thousands of steel wires twisted and bound tightly together. Steel is an ideal material for these cables because it can withstand tension. Studies show that a single steel wire only 0.1 inch thick is able to support more than one half ton without breaking.

Unfortunately, history has shown that suspension bridges aren’t unbreakable. Because they are so light and flexible, extreme winds and earthquakes have been known to damage and in some cases, destroy them.

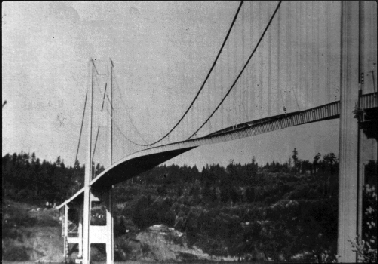

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge twisting in the wind prior to its collapse.

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge twisting in the wind prior to its collapse.

The ultimate example: The Tacoma Narrows Bridge was the third-longest suspension bridge in the world when it opened in 1940 in Washington state. It was soon given the nickname, “Galloping Gertie,” because of how it performed when it was windy. Not only did the deck sway back and forth, it also jumped up and down, even in only moderate wind conditions. It was so bad that drivers reported that vehicles in front of them would disappear and reappear from view as they crossed the bridge.

Several attempts were made to stabilize the structure using cables and hydraulic buffers. However, they were not successful. The bridge collapsed in a 42-mile-per-hour wind on November 7, 1940, just four months after it opened. Engineers had designed the bridge to hold up against winds of up to 120 miles per hour.

The failure had a big impact on the engineering community. After studying the collapse, most came to the conclusion that it was the result of resonance, the same phenomenon that causes glass to break at high sound frequencies.

After the Tacoma Narrows Bridge collapse, engineers began applying the science of aerodynamics to bridge design. Today, proposed designs must be wind-tunnel tested. This unfortunate incident ushered in an era of stronger, safer, and more elegant suspension bridge design.

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge is currently a pair of structures, one completed in 1950 and the other in 2007 to help relieve traffic issues.

The Tacoma Narrows Bridge is currently a pair of structures, one completed in 1950 and the other in 2007 to help relieve traffic issues.

The lessons learned were applied to the replacement for the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, which was finished in 1950. It’s wider than the original, has stiffening trusses under the roadway, and includes a narrow gap down the middle, all of which limit the effect of the wind.

The Akashi Kaikyo Bridge has the longest center span — 6,500-plus feet — of any suspension bridge on earth.

The Akashi Kaikyo Bridge has the longest center span — 6,500-plus feet — of any suspension bridge on earth.

The Akashi Kaikyo Bridge is currently the world’s longest suspension bridge. It links the Japanese city of Kobe on the mainland of Honshu to Iwaya on Awaji Island. It crosses the busy Akashi Strait as part of the Honshu-Shikoku Highway. It was completed in 1998 at a cost of $7.6 billion.

To maintain the stability of the structure, engineers added pendulum-like devices on the towers to keep them from swaying. They also included a stabilizing fin beneath the center deck to prevent damage from typhoon-strength winds.

Cable-Stayed Bridges

Cable-stayed bridges have a few things in common with suspension bridges. For example, both feature roadways that hang from cables and towers.

However, the two types of bridges support the roadway load in different ways, the key one being how the cables are connected to the towers.

With suspension bridges, the cables are strung freely across the towers, transmitting the load to the anchorages at their ends.

With cable-stayed bridges, the cables are attached directly to the towers, which handle the load. The cables can be connected to the roadway in two ways:

- In a radial pattern, with the cables extending from a single point at the top of the tower to several points on the road.

- In a parallel pattern, with cables attached to different points along the tower and running parallel to one another as they connect to the roadway.

Today’s cable-stayed bridges often look futuristic, and most people think they’re a new innovation. However, the idea for them goes back more than 400 years. The earliest known design for one appears in “Machinae Novae,” a book published in 1595.

It took until the 20th century for engineers to actually begin building them. The reason was necessity. After World War II, steel was scarce in Europe. The design turned out to be perfect for rebuilding bridges that were destroyed, because they used less steel that other alternatives.

Cable-stayed bridges started being built in the United States decades later. Today, they are popular because of their dramatic, futuristic designs.

In general, cable-stayed structures are best-suited for medium-length bridges, usually between 500 and 2,800 feet. Although longer cable-stayed bridges have been built, suspension bridges are still typically used for bigger spans.

Compared to suspension bridges, cable-stayed ones are generally faster to build and more cost effective. They’re less expensive because they require less cable and can be built from identical precast concrete sections. Despite this efficiency, cable-stayed bridges are beautiful.

The Sunshine Skyway Bridge is renowned for its dramatic profile and coloring.

The Sunshine Skyway Bridge is renowned for its dramatic profile and coloring.

One of the earliest examples of a noteworthy cable-stayed bridge in the U.S. is the Sunshine Skyway Bridge in Tampa, Florida. It was awarded the Presidential Design Award from the National Endowment for the Arts in 1988.

The bridge is painted a bright sunshine yellow, which plays against the water around it. It was one of the first bridges of its type to attach cables to the center of the roadway. Most earlier versions placed cables at the outer edges. This innovation gives drivers a clearer view of the surrounding bay.

The Leonard P. Zakim Bridge provides a grand entrance to the city of Boston.

The Leonard P. Zakim Bridge provides a grand entrance to the city of Boston.

One of the most famous — and widest — cable-stayed bridges anywhere crosses the Charles River in Boston, Massachusetts. The iconic structure, completed in 2002, has become a landmark in a city filled with them.

Officially named the Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge, the viaduct was a critical component of The Big Dig Project, which connected the city using a system of under- and above-ground roads and bridges. The Bridge serves as the impressive northern entrance to the city of Boston and is an ideal example of one perfectly suited to its location.